Beatriz Milhazes’ current solo exhibition, Rigor and Beauty, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, opened March 7th and will run through September 7, 2025. The installation of 15 works showcases the Brazilian artist’s evolution from 1995 to 2023. This collection illuminates Milhazes’ distinctive fusion of organic forms, layered compositions, geometric precision, and the vibrant distillation and celebration of Brazilian culture and music.

Having followed Milhazes’ work since her earlier exhibitions at the James Cohan Gallery, I often fondly recall her 2015 show, Marola, as particularly captivating. The title refers to the water ripples following a large wave and the reverberating rhythms found in water. The show balanced the artist’s layered paintings with large hanging sculptural artworks. Milhazes’ paintings and sculptures combined to create an environment where cross-cultural references can link concepts such as the Pattern and Decoration movement, botanical forms, geometric art, and Brazilian visual culture aesthetic. The unapologetic celebration of beauty, joy, and abundance in Milhazes’ work was striking.

Experiencing the artist’s first exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum is a real treat. Eight large paintings made between 1995 and 2022 fill the exhibition space, accompanied by a suite of seven collages made between 2013 and 2021. The earliest painting, Santa Cruz, dates back to 1995, coinciding with her inclusion in the Carnegie International held the same year. This was a pivotal exhibition that brought Milhazes global recognition. This painting shows motifs that mix indigenous and colonial ornamentation and becomes the touchstone starting point for viewing the artist’s growth and development through her work in the exhibition.

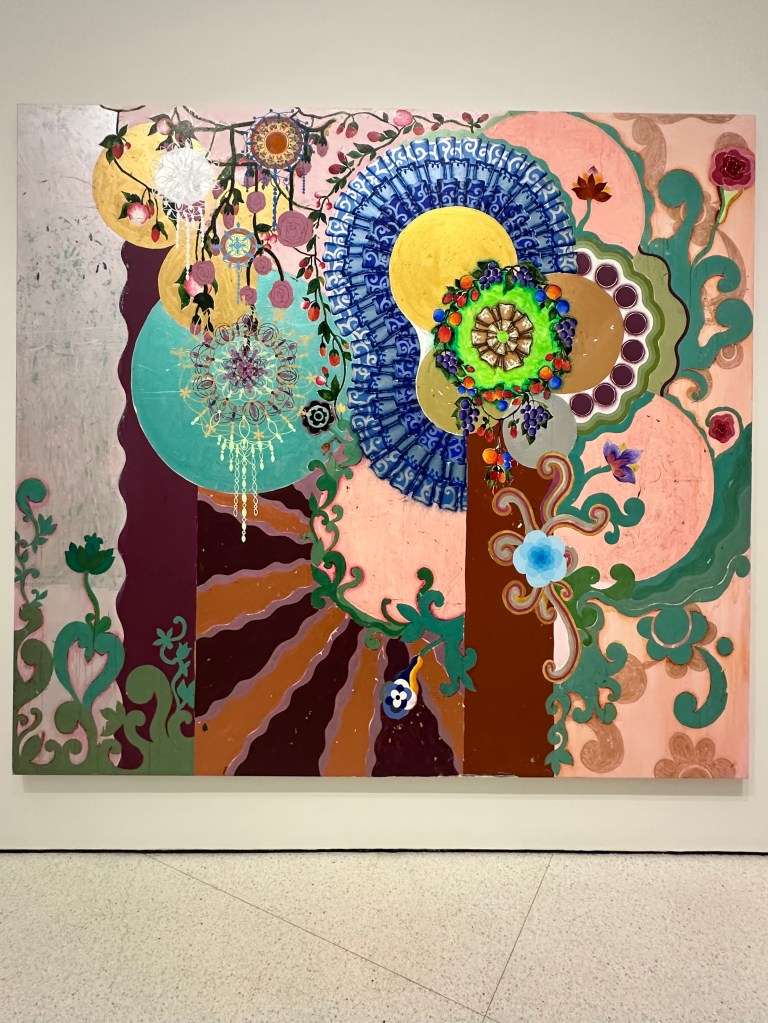

Milhazes’ technical approach involves layered imagery and precise hard-edge lines. She achieves this through her unique “monotransfer” technique. This process applies a collage logic to painting by first painting multiple individual and compound elements on thin plastic and then transferring the painted images to canvas. The resulting composition is an accumulation of shapes, colors, and motifs. Subtle imperfections and textural nuances are an interesting side effect of this otherwise meticulous process. Milhazes’ compositions blend floral patterns, arabesque structures, and frequent circular shapes with geometric elements, often reflecting the undeniable influence of her studio’s proximity to the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Gardens.

The works and their titles indicate Milhazes’ ruminations, especially regarding nature. For instance, in the painting The Four Seasons (1997), she explores Brazil’s lack of pronounced seasonal shifts as compared to, for example, what we experience in New York City. Another painting, The Carnation and the Rose (2000), my favorite in the show, pays homage to floral design, mystic geometry, feminine embroidery, Op Art, and notably includes a “Flower of Life,” evident in the use of a central prominent repeating pattern mandala-like monochromatic green flower with value gradation, that employs distinctly structured radial symmetry.

A perceptible evolution in Milhazes’ work is observed in the transition from earlier to later paintings in the exhibition’s nearly three-decade period. The older works demonstrate more compositional conflict with competing elements and varied brushwork, often resulting in a rougher surface quality. In contrast, the later works appear more refined and polished, mirroring the clean edges and solid forms characteristic of her smaller-scaled collage compositions on view.

Milhazes’ canvases are a symphony of color and form, a visual euphony where organic motifs intertwine with geometric structures. This interplay creates a rhythmic visual experience for a synesthetic echoing of the syncopation famously found in Brazilian music. Her work is clearly influenced by Brazilian culture, capturing the exuberance of Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival, especially with its dazzling displays of feathered and floral costumes and the continuation of the rich tradition of Tropicália. This movement melded popular culture and the avant-garde through art, music, and literature to advocate and celebrate Brazilian identity. One painting, for instance, is titled Carioca Landscape (2000), where the term Carioca refers to a resident or native of Rio de Janeiro and is unapologetically bold and exuberant in form and color.

The exhibition also highlights the contrast between her collage compositions and large-scale paintings. Milhazes’ collages have a slicker, more polished aesthetic, achieved through the meticulous layering of paper and ephemera elements such as candy wrappers and shopping bags. In contrast, her large-scale paintings reveal a more organic, handmade quality, with subtle imperfections and textural nuances underscoring the seductive facture achieved by the imperfections of the artist’s hand. In person, the paintings offer a tactile intimacy that invites the viewer to delve deeper into each canvas, which does not transfer as well in photographic reproductions of the work.

I was delighted to note that Milhazes infuses her abstractions with spiritual imagery, especially in her recent work. Drawing upon symbols and motifs that resonate on a metaphysical level, the layering of forms can be interpreted as a metaphor for the layers of human experience and consciousness. The paintings invite viewers to reflect on their own spiritual journeys through transcendental contemplation and abstract symbolism, much like in the work of Swedish painter Hilma af Klint, who had a phenomenal solo show at the Guggenheim Museum in 2018-2019.

Considering Immanuel Kant’s notions of beauty and grace, expressed through a free play of the imagination, Milhazes’ work embodies the idea that true beauty arises from the harmonious interplay of form and abstracted “disinterested” content. Her compositions achieve this balance, offering viewers an experience that is both sensually gratifying and intellectually stimulating gained through an intuitive perception of the artwork. The grace inherent in Milhazes’ work reflects a deft handling of aesthetic principles, aligning with Kant’s belief in beauty as a manifestation of purposiveness without purpose, evoking a subjective and universal pleasure.

Written by Katerina Lanfranco who is a painter based in NYC. She writes for POVarts and was a contributing writer for The Art Blog based in Philadelphia. Lanfranco teaches studio art and design at Parsons School of Design and Hunter College. She is also fascinated by the mystical and healing power of nature. You can follow her work on Instagram @katerinalanfranco and her curatorial work @rhombusspace